Way before Cassius Clay (later to be Muhammad Ali) was even a twinkle in his father’s eye an African American took the World Heavyweight Boxing Champion, the first African American to do so. The year was 1908 and Jack Johnson (born John Arthur Johnson) held the title for seven years. Many people have never heard of Jack Johnson, but his story is one which needs (or indeed begs) to be told.

His story also enables us to reflect on how much times have changed in so many ways – and yet in others hardly at all.

Johnson was born to Henry and Tina Johnson in Galveston, Texas in 1878. His parents were emancipated slaves and Henry, their first son was represented the first generation of his family to be born in to freedom. Yet times were tough. Although the parents worked a succession of blue-collar jobs yet still managed to teach their six children to read and write. Galveston only had about five years of formal education before he joined the tough world of the Galveston Docks as a general laborer.

Johnson developed his boxing technique in this environment, patient and defensive, he would lie in wait for his opponent to make a mistake and then he would go in for the kill. A cautious starter he would build up his aggression over a series of rounds and then continuously punish his opponents rather than go all out for a knockout blow.

The press of the day rounded on Johnson for his technique. Yet only a decade earlier they had praised “Gentleman” Jim Corbett, generally considered the father of modern boxing, for a very similar style. Johnson had studies the techniques of the 1892 World Boxing Champion and adapted them to his own style. Yet still the press condemned him for being devious. Clever and color it seemed, would not be rewarded.

His first title would come in 1903 – when he won a title that no one would contemplate these days – the World Colored Heavyweight Championship. Perhaps he could have won the World at that time but the champion of the time, James J Jeffries simply refused to fight him – on purely racially grounds.

Today, this would probably mean the end of someone’s boxing career and international vilification in the press. However in 1903 Jeffries was well within his rights. Other championships were open to black boxers but the world title was blocked, completely off limits. Not to be thwarted, in 1907 Johnson proved his mettle when he knocked out a former World Heavyweight Champion in the second round.

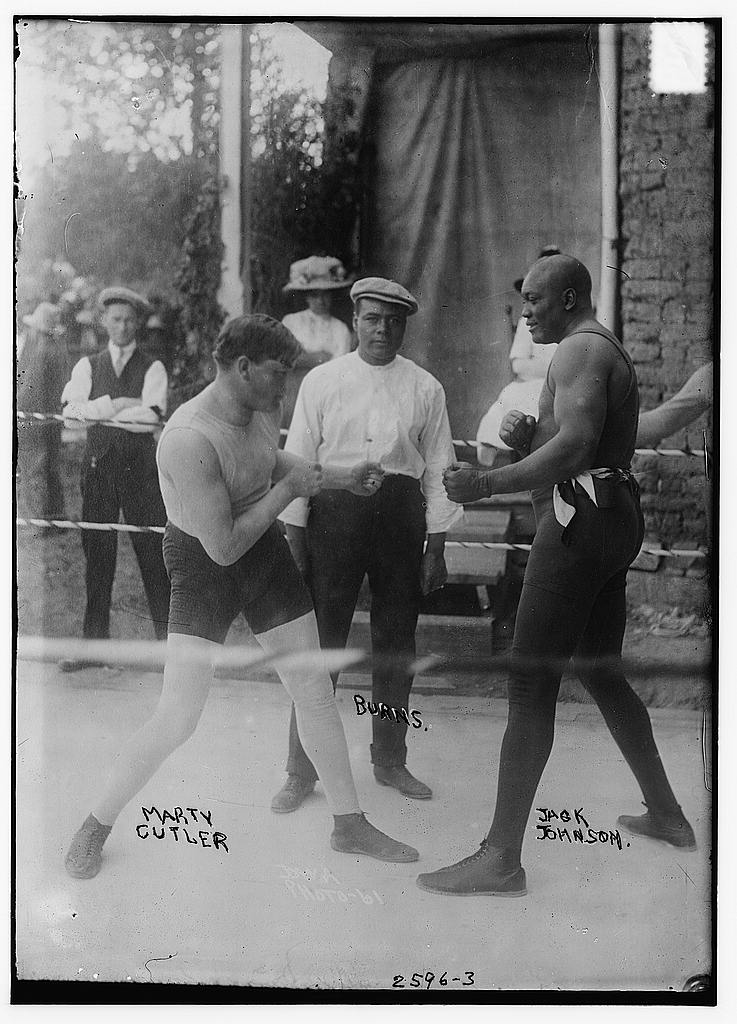

Johnson used a tactic familiar to us today in order to secure a match. He virtually stalked the world champion (the Canadian Tommy Burns) around the world and used the press (his old enemy) to taunt the boxer in to finally agreeing to fight him. Burns finally gave in and on Boxing Day 1908 the pair went head to head for fourteen rounds in front of over twenty thousand people in Sydney, Australia (see picture below). It was stopped by the police and the referee awarded the title to Johnson.

The referee deemed the win to be a Technical Knock Out (TKO) deeming Burns unable to continue. However, Johnson had clearly won the fight, having soundly beaten the champion particularly in the later rounds. The technicality must have made him furious but he had what he wanted – the Heavyweight Championship of the World.

There was an immediate and racial backlash towards Johnson in the press, who had happily printed his goads towards Burns but had not expected him to win. Jack London (who wrote Call of the Wild) was one of many who called for a Great White Hope to come along and beat Johnson. And so they did – many of them in exhibition matches.

While champion, Johnson lived the life of a celebrity and was forever in the press or on the radio. He was immensely popular - above, a crowd await his arrival in New York sometime between 1910 and 1915 (his poster appears bottom left).

He endorsed a great number of products and became a hobbyist, joining in the new fad for automobile racing. He was always immaculately and expensively tailored - and had a fine line in nouveau riche wit. When stopped once for speeding he gave the traffic cop a one hundred dollar note. The fine was fifty and the policeman protested that he had no change to give. Keep it, rejoined Johnson – I intend to make my return trip at the same speed.

The fight was arranged on a deliberately provocative date – July 4 – and was fought in Reno, Nevada in front of a capacity crowd of twenty thousand. Fifteen rounds later Jeffries’ team called it quits – Johnson had knocked him down twice already (a career first for Jeffries) and they did not want the black champion to knock him out. Here are the highlights.

Johnson retained his title and earned (for those days) an enormous $65,000. Yet the result of the fight was to have untold consequences. His retention of the title provoked race riots in more than 25 states and 50 cities, all on the fourth of July. Humiliated by his victory whites took the law in to their own hands and police had to stop several attempts at lynching.

Most of the riots began as black communities celebrated in the streets and the police and neighboring white retaliated through sheer spite. Chicago police, notably, allowed the celebrations to continue peacefully and the African-American poet William Waring Cuney was inspired to write My Lord, What a Morning. It is short, pointed and very funny.

O my Lord

What a morning,

O my Lord,

What a feeling,

When Jack Johnson

Turned Jim Jeffries'

Snow-white face

to the ceiling.

Johnson kept the title till 1915, when he lost it to Jess Willard, a Kansas cowbot. It went on for an amazing 26 rounds and ended with Johnson KO’d. By this point Johnson was 37 and past his peak. Yet Johnson’s name will live on forever in boxing history forever.

Johnson died in 1946 in a car crash near Franklington, North Carolina. He was 68. He had lost his temper in a local diner, had rushed out and got in his car – and ultimately lost his life in the crash. Why had he rushed so angrily out of the diner? They had refused to serve him – on the grounds of his color.

No comments:

Post a Comment